Every Generation is a Monetary Experiment

Just because money worked this way for most of your life...

My great-grandmother was born into a time when money was gold—no matter what country you lived in, the local currency was likely a proxy for real money. A dollar was exchangeable for a dollar worth of gold or silver. A dollar saved was thought to hold its value as well as precious metals because there was no reason to think that it wouldn’t be worth the same amount in gold or silver later—it said so right on the note! In fact, these notes weren’t even thought of as a unit of value in themselves so much as an IOU, exchangeable for real money. With a great trust in institutions, this belief held until she turned 32 and president Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102, making it illegal for individual citizens to own physical gold.

Of course, at the signing of these orders, barely anyone had any gold—or dollars for that matter—because the Great Depression had spent the prior 4 years wiping out the stock market, massively destroying jobs, crushing the economy, and eating away at whatever savings anyone could have stored (unless you had excessive amounts of money pre-crash). This clever timing allowed the federal government to hoard gold itself, in preparation for funding the next world war, without raising too many alarms by citizens who already had nothing to lose. This marks the point at which the US Dollar, though not yet legally/completely severed from gold, began the fiat monetary phase.

My great-grandparents were Canadian citizens, but even at this time, before the Canadian dollar pegged to the US dollar during WWII, the Canadian economy was tied shoulder to shoulder with the US, and as much at the mercy of the Great Depression as the rest of the continent. The banking policies enacted in the US were mimicked up north. A solidarity in financial policy meant uniformity of control—no gold would bleed out between borders as each government would buy it from any citizen who still had any gold to buy, and enforcement would be certain.

A few months after owning gold became outlawed, my grandfather was born, the youngest of five children—the final set of small hands to help feed the family with carpentry work. Luckily the Great Depression ended before he could do much more than hammer a nail and when he turned 15, the family immigrated to California where he built houses with his brothers and volunteered as a fire-fighter. A few years later, a great promise came in the form of the Korean war: Join to fight and become a US citizen! Two years of service later, he came back alive and naturalized, a 20 year-old with the stories of an old man. From that point on, he knew no financial world other than fiat currency. His prospects were clear, a job at Aerojet General Corporation absorbed his post-war talent and paid him fiat currency for over 30 years. He even got a little bit of real money in the form of silver after working on the Apollo mission and receiving a Silver Snoopy from NASA—but this trinket was simply memorabilia—who would even think of it as a store of value? He married and had five kids just as his parents had done, traveled, gambled, watched sports, and built things with wood until he passed. His life was all he could have hoped, and maybe more. He owned a home, a car, had a family, was alive during the birth of credit cards, but great-grandma’s tutelage or perhaps just the timing made that evolution of money seem strange and disagreeable, if not merely unnecessary for the security of regular paychecks, a fairly steady affordable living, and a predictable, guaranteed retirement outcome.

My mother, the second youngest of the five children, was born only one year after the 1958 introduction of credit cards, which promised to revolutionize the concept of wealth. She was only eleven In 1971, oblivious to the destructive future effects Nixon Shock, the closing of the Gold Window, solidifying the fiat reality that had already consumed the world. The knock-on effects of disconnecting money from value has wide implications that we can see in 20/20 hindsight by asking the tongue-in-cheek question WTF Happened in 1971? Charts showing productivity exploding upward but wages stagnant are just the tip of the iceberg.

By the time she reached adulthood, two children before 20, welfare, food stamps and government housing got her through college. Aid programs kept us from living in our car (discounting the day or two sleeping overnight as we traveled between housing across state lines). The credit card debt form of money was, by absolute necessity, the primary way to spend money. It was no longer an IOU from the government to the citizen, but an IOU from the citizen to the corporation—a promise to help pull you out of a hole when you need it, if you promise to pay a high rate of interest, consuming the unwitting consumer into a type of indentured servitude, servile to a debt master, until the debts would be sold to a new master at a new rate, and the hole would never shrink, but get bigger and bigger. For her generation, and those in the following Gen X who got stuck in the same net, the word “fiat” doesn’t even compute as a monetary concept (isn’t that a car?)—gold is too archaic, bitcoin too technical, and why/how would you own a hard currency when you are in a perpetual state of debt?

I learned a lot of things from the experience of growing up with government aid and debt, which, along with a healthy hatred for camping and obsession with avoiding homelessness, kept me from ever holding a credit card balance beyond the due date (though it was extremely difficult). Now, as a member of the affluent class, I’m on the privilege end of the credit system now—using this form of money gives a 3-5% cash back discount and allows 30 days of deferred payment, during which time I make a risk-free return on the cash. But I only use this form of payment when I have the cash earning interest already on the sidelines, ready to auto-pay. I’ve avoided the 28% APR debts that surround my mother and many other members of my generation. Some of us had opportunity to take advantage of this form of money—having had a little bit of time to absorb and witness the consequences, and to do whatever else it took to avoid the trap (it took a lot). I was also fortunate to reap benefits from the Global Financial Crisis, owning 2 houses by that time, which didn’t go underwater, and selling them only much later, making decent profits from it, and then buying another house, and another. But as time goes on, I’m finding it harder to make sense of it all, and I’ve spent thousands of hours over the last decade, reading books about economics, listening to podcasts, absorbing charts, and historical data, writing my own spreadsheet models and code. It is pure madness. The recurring conclusion is that the foundational principles of our monetary system are completely upside down. Among many economic rabbit holes, Jeff Booth’s work on Deflationary economics is well worth the journey. The system is not sustainable. It will fail (again).

“Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.” - Kenneth Boulding

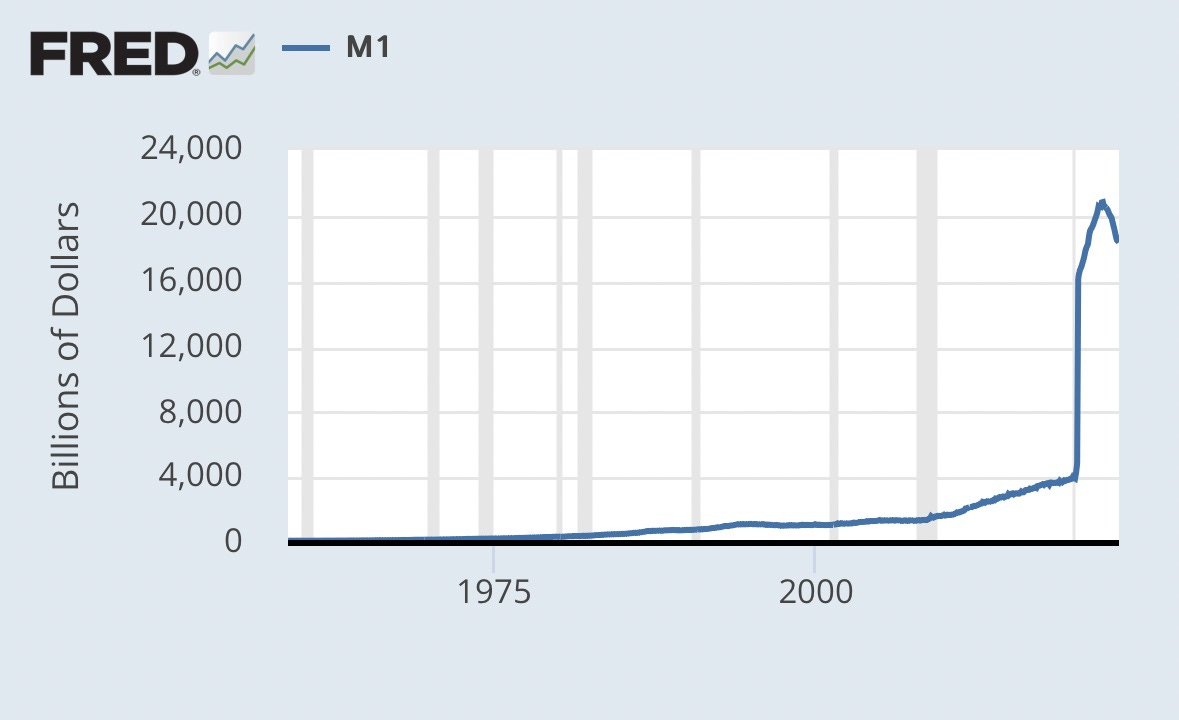

My daughter was born right into the Global Financial Crisis. Her life as it pertains to money has been dominated by the advent of Quantitative Easing and she has witnessed inflation first hand after a sudden printing of 16 trillion dollars!

She’s seen the parabolic rise of money (the dilution of value):

She’s seen that money is growing at 7 times the rate of humans on the planet (timecode link to video below):

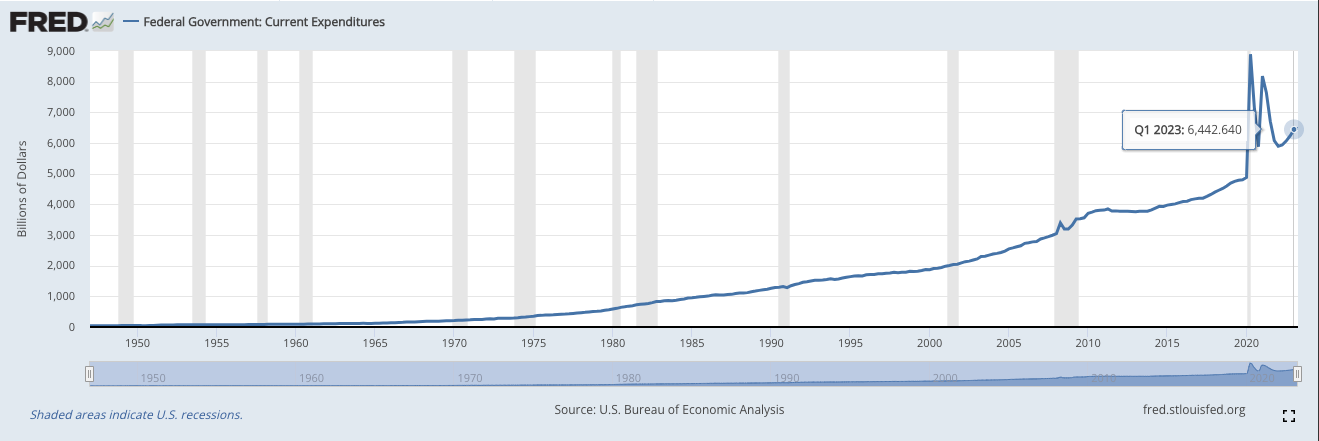

She’s seen that the federal government is spending $6.4T/year:

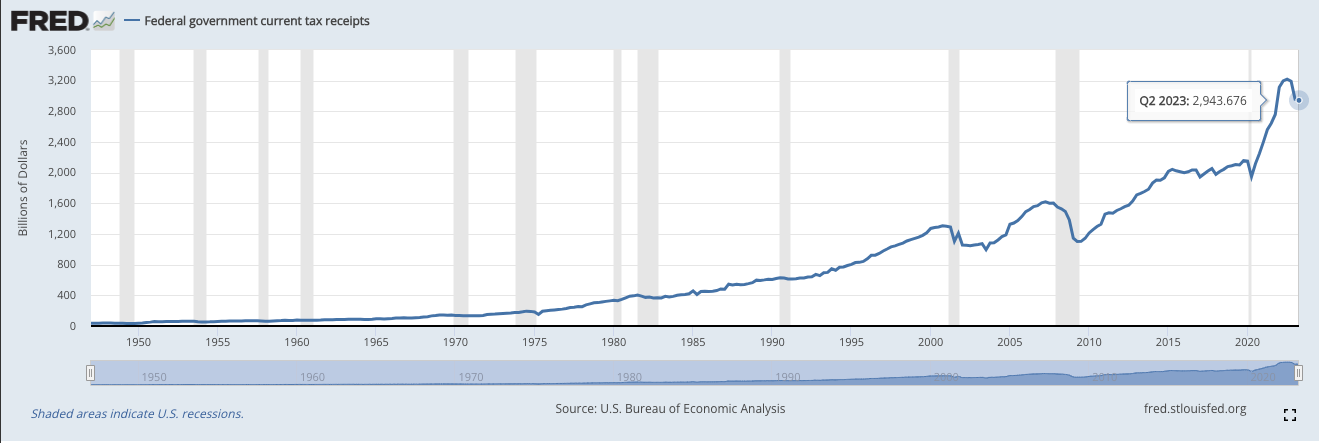

And that it’s only pulling in $2.9T/year in tax income, meaning that the remaining $3.5T/year is digitally printed, resulting in theft of value from the poor in the future to fill the gap:

She has also lived within the advent of Bitcoin, and Central Bank Digital Currencies (which will allow a government to distribute UBI at a whim, and to extract, halt transactions, or sanction individuals with zero notice or process).

Money is changing rapidly. New technologies are forming around us in realtime. Like climate change, it’s not so much that the change is happening that’s worrisome (as it was going to happen eventually anyway), it’s the speed of the change that is so disruptive and potentially apocalyptic—and it’s the wonton disregard for consequences by people making policies that are so aggravating. Politicians will continue to promise free things because that’s how you get elected. We will eventually attempt some form of UBI, even though it will most certainly lead to massive inflation—and it will increase the wealth gap rather than tighten it (topic for another time). We need time to adapt, to learn, to absorb new ways of understanding economics before these systems engulf and control us in ways we couldn’t foresee. Hindsight will provide charts for future generations to show how mad we were.

The only thing I’m sure of is that my grandchildren will have a completely different concept of money than anything we can imagine today.

![Adam Eivy \[._.]/'s avatar](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lg7t!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc81206b2-d085-49fc-a32c-e529b9bfd016_400x400.jpeg)